The Negroni (a drink made of equal parts gin, sweet vermouth, and Campari) and the Boulevardier (the same but with bourbon instead of gin) are the cocktail equivalent of Masonic handshakes. They have become the secret symbols that signify one practices the craft — the craft cocktail, that is.

And yet there is a great mystery to this duo. The Negroni is of venerable vintage, a cocktail standard in Italy for about a century but unknown in the States until well after WWII. As for the Boulevardier, it never gained any sort of foothold, neither in the U.S., nor in Paris (where the first and only reference to the drink can be found in the 1920s). The Boulevardier doesn’t even seem to have been known in Italy. The Boulevardier is the strangest of standard cocktails, one that, in its day, never had a day. It is a Jazz Age obscurity that didn’t catch on until it somehow became ubiquitous eight decades after it was originally composed.

The original, ever so brief appearance of the Boulevardier comes in Barflies and Cocktails, a 1927 book promoting Harry’s New York Bar in Paris, an essential watering hole. In this little book, bartender Harry MacElhone provided the drink recipes and ex-pat society columnist Arthur Moss contributed color commentary. One of the regulars at the bar was writer Erskine Gwynne, who was trying to get a monthly magazine off the ground. He called the publication the Boulevardier. Its slogan: “the magazine that is read be- fore, between, and after cocktails.” How better to promote a magazine so described than with a cocktail of the same name? Which is exactly what publisher Gwynne did: “Now is the time for all good Barflies to come to the aid of the party,” Moss wrote, “since Erskinne Gwynne crashed in with his Boulevardier Cocktail; 1/3 Campari, 1/3 Italian vermouth, 1/3 Bourbon whisky.”

Alas, the cocktail, like the magazine, went nowhere.

Consult essential midcentury cocktail books and you will find references neither to the Negroni nor to the Boulevardier. The drinks are absent in Patrick Gavin Duffy’s 1940 drinks compendium, The Bartender’s Guide, they didn’t even find a place in the book when it was revised and enlarged by James Beard at the end of that decade. Among the 700 recipes in David Embury’s authoritative 1948 book, The Fine Art of Mixing Drinks, there is no Negroni and no Boulevardier. (There is, however, an entirely unrelated cocktail called the Boulevard, a dry Manhattan with a few splashes of Grand Marnier.)

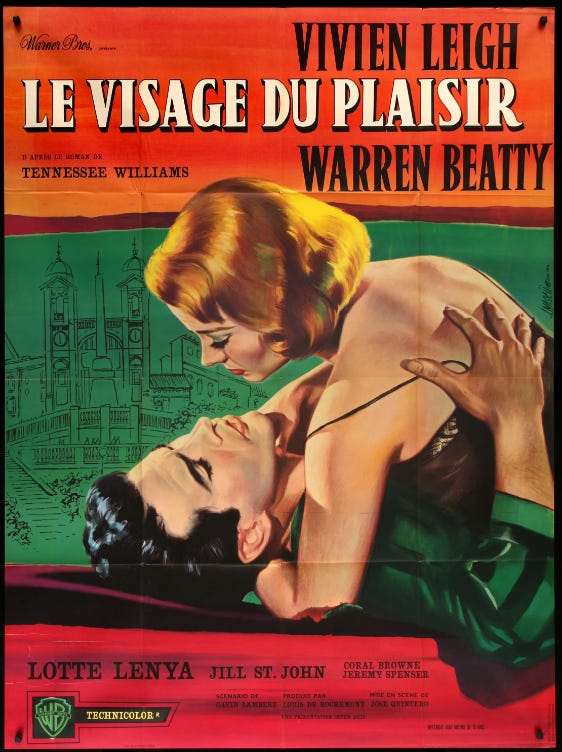

The Negroni, however, did have an organic following in Italy. And, come the '50s, the marketing folks at Campari launched a campaign to make the Negroni an expression of Italian chic. The drink is touted in such mid-'50s travel guides as Footloose in Italy, Roman Holiday, and When in Rome. In 1957, Cosmopolitan raved, “Almost every member of the international set sooner or later lands at one of the sidewalk tables of Doney’s on the Via Veneto for an aperitif — usually a Negroni.” But for all the advertising, PR placement, and hype, Campari stuck with just a few cocktails — the Negroni, the Americano (a Negroni without the gin), and the Cardinal (a Negroni with dry vermouth instead of sweet vermouth). The Negroni was established in the States, with a little help from the 1961 movie The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone, in which the drink is a symbol of seduction.

Still, there was no Boulevardier in sight.

Until, that is, one of the pioneers of the classic cocktail renaissance gave Barflies and Cocktails a careful read. Ted Haigh, better known as “Dr. Cocktail,” found the reference to Gwynne and his Boulevardier. He devoted a page to the drink in the 2009 edition of his influential book Vintage Spirits and Forgotten Cocktails. And thus, a drink that was more than forgotten — it would be more accurate to say it was never remembered in the first place — became an emblem worn by the cocktail cognoscenti, a way of signifying their membership in the club.